When the Rules Change

On my return home to Newport after two weeks at the Lambeth Conference in England, I found my garden in a riotously abundant condition. It was teeming with tomatoes of every variety I know — gorgeous round, red hybrids like Better Boy and Beefsteak, along with heirlooms like Black Krim, Cherokee Purple, and Mr. Stripey. There were great big globular fruits larger than softballs and smaller cherry tomatoes of all varieties, as well as tiny grape tomatoes. The garden is chaotic, completely uncontained, and I’m not at all in control. And the crook-necked squash vine — which, by the way, I DID NOT PLANT — has now escaped the bounds of the garden fence and is bursting out in blooms and fruit all over the back yard, with all the energy and surprise of fireworks in the summer night sky. None of the tomatoes, cucumbers, or other vegetables I planted myself survived, but I think I finally understand why there is such glorious bounty nonetheless. It’s as extravagant as the Sower of Seeds in that old Pete Seeger song, and maybe even wasteful if you count all the tomatoes I can’t reach.

On my return home to Newport after two weeks at the Lambeth Conference in England, I found my garden in a riotously abundant condition. It was teeming with tomatoes of every variety I know — gorgeous round, red hybrids like Better Boy and Beefsteak, along with heirlooms like Black Krim, Cherokee Purple, and Mr. Stripey. There were great big globular fruits larger than softballs and smaller cherry tomatoes of all varieties, as well as tiny grape tomatoes. The garden is chaotic, completely uncontained, and I’m not at all in control. And the crook-necked squash vine — which, by the way, I DID NOT PLANT — has now escaped the bounds of the garden fence and is bursting out in blooms and fruit all over the back yard, with all the energy and surprise of fireworks in the summer night sky. None of the tomatoes, cucumbers, or other vegetables I planted myself survived, but I think I finally understand why there is such glorious bounty nonetheless. It’s as extravagant as the Sower of Seeds in that old Pete Seeger song, and maybe even wasteful if you count all the tomatoes I can’t reach.

What does it mean not to be in control? What does it feel like, when everything you’ve ever learned, and every gardening standard you’ve ever been judged on, tells you that the tomatoes should be spaced 24 to 36 inches apart, and never planted where tomatoes — or eggplants or potatoes — have been planted in the past two years, and yet the abundant life in the garden actively resists these learned, scientific constraints, not just once, but year after year? From a transactional lawyer’s — or even a rector’s — point of view, this garden is disorganized and inefficient. In a gardener’s careful plan for ease of harvest, even access to sun and careful spacing for root development, tomatoes belong in neat little rows, 24 to 36 inches apart. This self-seeding, anarchic garden defies both science and tradition, as well as wasting all of the tomatoes that I can’t even reach through the thickets of vines. But those tomatoes I can’t reach reseed the garden for next year, so I’m pretty sure nothing is wasted in God’s economy, even though I’m not in control of the bottom line.

The Pharisees and the Sabbath

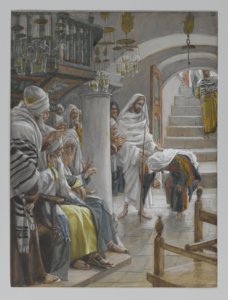

I wonder how the Pharisees felt when Jesus healed the woman who had been bent down for 18 years by an unclean spirit? After all, there’s a time and place for that kind of thing — maybe in the unclean spirit healing place, during office hours. But certainly not in the synagogue, and not on the Sabbath. And just to make this point clear, Luke’s gospel mentions the sabbath 5 times, hinting at it two times more, in this one little passage. There’s no question that health is good and being bent over at the waist for 18 years like the woman in the story is bad and needs to be fixed. We’re supposed to notice that time, place, and manner are at stake here, not healing. It’s easy to distinguish between good and evil, and Luke’s gospel makes sure that we understand that the conflict here is not over what is good, but how — and when — to get to that good.

I wonder how the Pharisees felt when Jesus healed the woman who had been bent down for 18 years by an unclean spirit? After all, there’s a time and place for that kind of thing — maybe in the unclean spirit healing place, during office hours. But certainly not in the synagogue, and not on the Sabbath. And just to make this point clear, Luke’s gospel mentions the sabbath 5 times, hinting at it two times more, in this one little passage. There’s no question that health is good and being bent over at the waist for 18 years like the woman in the story is bad and needs to be fixed. We’re supposed to notice that time, place, and manner are at stake here, not healing. It’s easy to distinguish between good and evil, and Luke’s gospel makes sure that we understand that the conflict here is not over what is good, but how — and when — to get to that good.

The Pharisees were not bad people. They were the very observant, faithful, learned sect of Jews who always showed up to worship, kept the fasts, said their prayers — kind of like all of us today who come to church and always remember to pledge. It’s hard to live in a world where the rules are changing and where what we’ve always done before doesn’t work any more. I can really relate to the Pharisees’ discomfort, and from the content of the news every single day, I don’t think that I’m the only one who feels confused and a little threatened. And I think it might help us to walk openly in the Pharisees’ sandals for a minute here. In this story, all the Pharisees wanted was to be good people before God, and they and the generations before them had spent their whole lives learning the applicable rules to do just that. Their whole way of life is called into question when Jesus makes the common sense point that healing on the sabbath in the synagogue is the moral and theological equivalent of untying their ox or donkey to allow it to reach water to drink.

Our Alter Egos – the Pharisees

And yet … Are we missing something if we immediately rejoice that the tables are turned on the Pharisees’ expectations? The narrative setup in this story is almost requires us to side with Jesus, but scripture is subtle, layered and deep, and I think we might miss an important insight into our lives and attitudes if we don’t own up to our alter egos in this drama — the Pharisees — who are just trying to do the right thing in the context they know. As preacher Elizabeth Palmer says, this rejoicing can harden into punitive judgment… and people we disagree with become enemies to be vanquished. Once those we disagree with become “the other,” it’s easy to feel that we can’t be right and hold onto our own truth and our own experience unless the other (those who disagree) are wrong — wrong about God, wrong about how to worship, or wrong about politics.

If we can’t allow the truth of another’s context and experience, and in order for us to be right, someone else has to be wrong, we find ourselves on a constantly shifting seesaw of glory and shame. We seek always to be on the side that is rising, with everyone else who’s wrong on the down side, but this way of living in the world is not only destabilizing and uncertain, it also bases all of our relationships in judgment rather than grace. Our opportunity is to understand our different contexts and be ready to walk in the other’s sandals for a while. Coming from different contexts — or seeking to remain in a context that no longer actually looks like our surroundings now — doesn’t necessarily mean one side is wrong. Like the good in my chaotic, unruly garden, more than one thing can be true at a time. You don’t have to be wrong for me to be right.

If we can’t allow the truth of another’s context and experience, and in order for us to be right, someone else has to be wrong, we find ourselves on a constantly shifting seesaw of glory and shame. We seek always to be on the side that is rising, with everyone else who’s wrong on the down side, but this way of living in the world is not only destabilizing and uncertain, it also bases all of our relationships in judgment rather than grace. Our opportunity is to understand our different contexts and be ready to walk in the other’s sandals for a while. Coming from different contexts — or seeking to remain in a context that no longer actually looks like our surroundings now — doesn’t necessarily mean one side is wrong. Like the good in my chaotic, unruly garden, more than one thing can be true at a time. You don’t have to be wrong for me to be right.

Our awareness of, and respect for, different truths do invite us to unbend our spines and stand up straight — to be healed by Jesus — if we have been bound by rules, practices, and understandings that no longer fit our reality. The woman with the bent spine had been that way for 18 years. Eighteen years ago was 2004. While many of our attitudes and understandings are based on circumstances from even further back in our lives than 2004, can you think of anything that was true for you in 2004 that may have changed in the 18 years since then? We can see much better when we unbend ourselves from experiences that have become contortions in the current world.

Look Outwards

In a post-Lambeth Conference summary this past week, the Archbishop of Canterbury described the two aims of the Lambeth Conference: First was renewal of spiritual life amongst the bishops and spouses. Second was to turn to face outwards after decades of looking in at ourselves. The best way of dealing with internal challenges is to seek God. It is God who turns us to serve God’s mission in the world — and contextualise our internal struggles in the knowledge of the overwhelming horror and suffering. Archbishop Justin continued, the Conference was a success: not because it produced a great outburst of agreement, but because it showed, in a very fractured world, that disagreement without hatred is possible, diversity is a gain not a problem, and that we can find greater organic unity if we look outwards and give ourselves to… [God’s mission in the world].

As island dwellers ourselves, even though we’ve thrived for generations with energy uses and conveniences that have improved our standard of living, we can understand the climate emergency our own context and see that we need to do our part to change. What happens when we unbend our spines and look outwards instead of looking in on ourselves? What can we at Emmanuel Church do to make a difference for our environment? At our vestry meeting this week, one vestry member suggested that we establish a community container garden in the church yard, to invite the whole community around us into a project to conserve water while growing food. Watering our lawn, which feeds only our resident rabbits, takes dwindling and increasingly expensive fresh-water resources in this fragile earth, our island home, as our eucharistic prayer poetically casts our opportunity for climate repentance.

Would a container garden in our church yard like that make all the difference the world needs? Maybe not, but I think it could make a world’s difference in each of us. As God told the Prophet Jeremiah in our reading this morning, Do not say, ‘I am only just [me]; for you shall go to all to whom I send you, and you shall speak whatever I command you. Do not be afraid of them, for I am with you to deliver you. “Now I have put my words in your mouth. See, today I appoint you over nations and over kingdoms… to build and to plant.” Amen