The View From the Top of the Sycamore Tree

Later this afternoon, I head off to London for the week in what has been an annual ritual for me for the past 14 years. The Compass Rose Society, a mission organization supporting the Archbishop of Canterbury’s ministry of relationship in the global Anglican Communion, has its first in-person meeting since the Fall of 2019 next week. We’ll be meeting at the Anglican Communion Offices in Knotting Hill near the famous Portobello Road street market, and at Church House near Westminster Abbey, concluded by dinner at Lambeth Palace with Archbishop Justin and Mrs. Carolyn Welby. I am the chancellor, or legal advisor, of the Compass Rose Society, as well as a member of the Executive Committee, and I have an active role in both the board meeting and the annual general meeting of members. While I’m in London, I’ll also be working with Lambeth Palace staff to incorporate the bishops’ feedback from the Lambeth Conference into the Reconciliation Call, one of the nine conversational follow-ups from this summer’s Lambeth Conference of Bishops at the University of Kent in Canterbury, England.

Later this afternoon, I head off to London for the week in what has been an annual ritual for me for the past 14 years. The Compass Rose Society, a mission organization supporting the Archbishop of Canterbury’s ministry of relationship in the global Anglican Communion, has its first in-person meeting since the Fall of 2019 next week. We’ll be meeting at the Anglican Communion Offices in Knotting Hill near the famous Portobello Road street market, and at Church House near Westminster Abbey, concluded by dinner at Lambeth Palace with Archbishop Justin and Mrs. Carolyn Welby. I am the chancellor, or legal advisor, of the Compass Rose Society, as well as a member of the Executive Committee, and I have an active role in both the board meeting and the annual general meeting of members. While I’m in London, I’ll also be working with Lambeth Palace staff to incorporate the bishops’ feedback from the Lambeth Conference into the Reconciliation Call, one of the nine conversational follow-ups from this summer’s Lambeth Conference of Bishops at the University of Kent in Canterbury, England.

Lambeth Conference

Just as a reminder, the Lambeth Conference, along with the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Primates of each of the Provinces, and the Anglican Consultative Council — the body of clergy and lay people elected and appointed from each of the 42 Provinces in the 165 countries of the Anglican Communion — is one of the four organizations that hold the Anglican Communion together, keeping us all in relationship. The Lambeth Conference has taken place about every 10 years or so since 1867, gathering all the bishops and spouses from all over the world who are in communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury. Over 600 bishops, and their spouses, gathered this summer in Canterbury. It had been 14 years since they last gathered, as COVID travel restrictions and some of the thorniest human questions of authority and power in the church delayed the conference.

Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, the chair of the Design Team for the Lambeth Conference, invited me last January to serve on the Reconciliation Call committee. The work of our committee was to prepare one of the nine discussion topics — ours was Reconciliation — for the bishops’ work of reflection, prayer, and conversation across their many different backgrounds and contexts. I was asked to be the committee’s scribe, listening carefully to the different voices, contexts, and experiences of the committee members to express the scriptural foundation and holy hope for the bishops’ conversations on Reconciliation.

Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, the chair of the Design Team for the Lambeth Conference, invited me last January to serve on the Reconciliation Call committee. The work of our committee was to prepare one of the nine discussion topics — ours was Reconciliation — for the bishops’ work of reflection, prayer, and conversation across their many different backgrounds and contexts. I was asked to be the committee’s scribe, listening carefully to the different voices, contexts, and experiences of the committee members to express the scriptural foundation and holy hope for the bishops’ conversations on Reconciliation.

The Reconciliation Call was — at least from my perspective — the main event at the Lambeth Conference. Consider the backdrop of the conference: the more liberal churches of the West, from a context of relative economic and political stability, were striving to honor individual rights and all expressions of identity, while in Africa, South America, and the Middle East, the church itself is often the greatest source of economic and political stability, and they are more likely to hold fast to tradition. It’s all way more nuanced and complicated than that, of course, but with just that example, you can see why conversation among the bishops at the Lambeth Conference was important.

Made in the Image of God

Their contexts, experiences, and perspectives were as different as the many colors of their skin, the variation in color and style of their national dress, and their many languages. With each of us made in the image of God, our very diversity allowed us all to see God more fully than we could have done if we remained isolated in our own contexts and saw things only from our own perspectives and experiences. Using the same Habits of a Reconciler that The Rev. Canon Sarah Snyder shared with the bishops at the Lambeth Conference and with us here at Emmanuel earlier this month, the bishops listened intently to one another, without judgment. They wondered actively about how the other’s context affected their perspective, and allowed their own perspectives to be changed by what they heard.

Their contexts, experiences, and perspectives were as different as the many colors of their skin, the variation in color and style of their national dress, and their many languages. With each of us made in the image of God, our very diversity allowed us all to see God more fully than we could have done if we remained isolated in our own contexts and saw things only from our own perspectives and experiences. Using the same Habits of a Reconciler that The Rev. Canon Sarah Snyder shared with the bishops at the Lambeth Conference and with us here at Emmanuel earlier this month, the bishops listened intently to one another, without judgment. They wondered actively about how the other’s context affected their perspective, and allowed their own perspectives to be changed by what they heard.

After an enormous controversy in the press and among the bishops over tablets designed to record the bishops’ support for the Calls overshadowed any useful discussion in the first two of the nine conversations, Archbishop Justin and the Design Team lived out the Habits of a Reconciler themselves. They listened — intently and without judgment, wondering actively how the other’s context shaped their perspective, and allowed their own perspectives to be changed by what they heard. They got rid of the “voting machines,” as the press was referring to the recording tablets.

We met as the Reconciliation Call committee the morning of the Reconciliation plenary and Call discussion, and instead of a show of hands, or a voice vote of support for the Reconciliation Call, we developed a concluding liturgy, honoring the holiness of our gathering. After the Reconciliation conversation, Archbishop Thabo spoke to the over 600 assembled bishops. He asked the bishops to rise — as and if they were moved by the Holy Spirit — to offer their commitments to reconciliation, each to the other and to God. Those of us on the committee watched from the back of the enormous room — translation booths lining both sides. It seemed that the whole room breathed in together as the bishops rose as one, unanimously affirming their commitment to the Reconciliation Call. I saw tears in the eyes of the bishops in the room through my own tears.

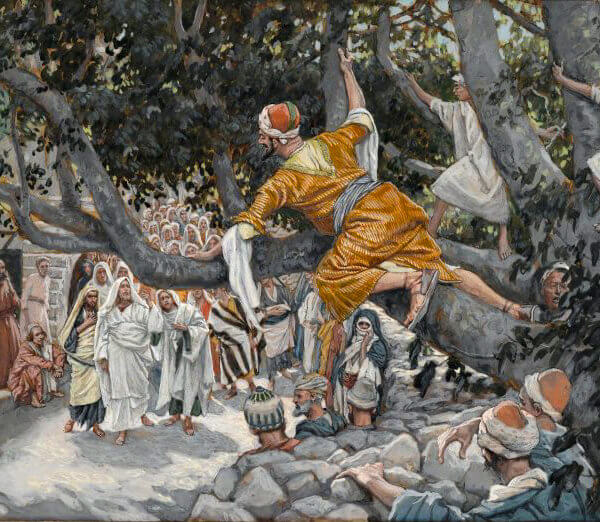

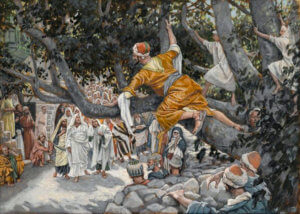

Zaccheus

I saw our gospel story of Zecchaeus in a whole new way after revisiting our work on the Reconciliation Call this week. The story is packed with detail, giving us tons of information about how the diminutive Zacchaeus’s encounter with Jesus in Jericho changed lives and built a community. What must it have felt like to be Zacchaeus, and to see things from his point of view? Zacchaeus is not just any tax collector. He’s the chief tax collector, and he’s rich. He got rich — as tax collectors did in the Roman Empire — by collecting more than what was owed from people who couldn’t afford to pay and then keeping the difference.

As if that’s not enough to separate him from relationship with others, he’s short, and he can’t see Jesus over the crowd. Luke’s gospel tells us specifically that Zecchaeus is short, because it creates the visual of someone who has already distanced himself from society economically and socially by climbing over them for his own advantage, now running ahead of them and climbing a tree to get even higher above them to see Jesus. Theology professor Brian Bantum wonders whether Zacchaeus’s sense of isolation from the community keeps him from recognizing the power he actually holds — and more importantly, the way that power is drawn away from the community he’s part of.

As if that’s not enough to separate him from relationship with others, he’s short, and he can’t see Jesus over the crowd. Luke’s gospel tells us specifically that Zecchaeus is short, because it creates the visual of someone who has already distanced himself from society economically and socially by climbing over them for his own advantage, now running ahead of them and climbing a tree to get even higher above them to see Jesus. Theology professor Brian Bantum wonders whether Zacchaeus’s sense of isolation from the community keeps him from recognizing the power he actually holds — and more importantly, the way that power is drawn away from the community he’s part of.

Maybe this is the important thing Jesus notices about Zecchaeus when he sees him up in that sycamore tree as he walks into Jericho: a man who has lost his sense of what it means to belong. Zecchaeus has separated himself from the community through his choices, and his relative economic and political comfort and stability have made his perspective and context very different from others and kept him from being part of the community.

After all, he’s looking down on Jesus from up in a sycamore tree, as the whole community gathers below to greet Jesus as he walks into town from his home on the Sea of Galilee. Jesus looks at Zacchaeus up in the tree and tells him, I need to come stay at your house. Zacchaeus climbed up in the sycamore tree because he wanted to see who Jesus was, and Jesus showed him just that, by coming to his house and pulling the community together. After Jesus invited himself over to Zacchaeus’s house, Zacchaeus suddenly stopped and listened — intently and without judgment, wondering actively how the community’s context affected their perspective, and allowed his own perspective to be changed by what he heard.

After all, he’s looking down on Jesus from up in a sycamore tree, as the whole community gathers below to greet Jesus as he walks into town from his home on the Sea of Galilee. Jesus looks at Zacchaeus up in the tree and tells him, I need to come stay at your house. Zacchaeus climbed up in the sycamore tree because he wanted to see who Jesus was, and Jesus showed him just that, by coming to his house and pulling the community together. After Jesus invited himself over to Zacchaeus’s house, Zacchaeus suddenly stopped and listened — intently and without judgment, wondering actively how the community’s context affected their perspective, and allowed his own perspective to be changed by what he heard.

Suddenly — with Jesus — the people Zacchaeus ignored or used are in his home. Jesus has broken down the barrier and torn apart the stories Zacchaeus told himself. Jesus shows him what true recognition and community look like. He shows him a bundle of life. And Zacchaeus responds with new insight and generosity. He welcomes, he shares, he joins, and he is bound up in the life of the community.

How can we come down from our own sycamore trees — our different contexts, views and perspectives — to listen fully to one another, wondering about the experiences that shape our perspectives, and allowing our views to be changed by what we hear? Our salvation is not through isolation to preserve our own perspectives on the world, each of us looking down from the top of our own sycamore tree. Our salvation is in our connection to each other, and our recognition of what we each might contribute to the flourishing of our community to participate fully in God’s abundant life. Amen