What Price Good News?

Scripture: Isaiah 43:1-7; Psalm 29; Acts 8:14-17; Luke 3:15-17, 21-22

Good morning, church. It is a joy to be with you again today, and I am grateful to all of you, and to my dear friend, Della, for inviting me. I’m also grateful to Della for the care and love she is showing all of us by staying home as she completes her recovery.

Please join me in prayer: May the words of my mouth, and the meditations of all our hearts, be acceptable to you, O Lord, our rock and our redeemer. Amen.

Would you like to hear some good news? I thought so; me, too. OK, here it is, from John the Baptist: “‘I baptize you with water; but one who is more powerful than I is coming; I am not worthy to untie the thong of his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, to clear his threshing floor and to gather the wheat into his granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire.”[1]

Would you like to hear some good news? I thought so; me, too. OK, here it is, from John the Baptist: “‘I baptize you with water; but one who is more powerful than I is coming; I am not worthy to untie the thong of his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, to clear his threshing floor and to gather the wheat into his granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire.”[1]

How do you feel when you hear this? Just this past Thursday, on Epiphany, Jesus was a sweet little child in his mother’s arms, receiving gifts and homage from the wise men. And now here He is, a mere three days later, brandishing a winnowing fork, burning chaff with unquenchable fire.

Does this sound like good news to you? Because it’s meant to be. Luke tells us so, in the very next verse: “So, with many other exhortations, [John] proclaimed the good news to the people.”[2] Our Lectionary skips this verse. It also skips the next two verses,[3] in which one person – King Herod – decides John’s news isn’t good at all. John has been giving Herod a hard time, you see; he has even dared to “rebuke” the king, not only for marrying his brother’s wife – a salacious detail that tends to stick in our minds – but also for “all the evil things Herod had done.” Good news? Herod is having none of it. Instead, he doubles down on his sin by throwing John into prison.

Well, none of us wants to be King Herod. And we do want good news. What would it take for us to receive John’s message – winnowing fork, wheat and chaff, unquenchable fire – as good news – as gospel, as glad tidings of great joy?

What price good news?

Here’s one answer: make someone else pay the price. Some of us are wheat; others are chaff. Some of us get gathered into Jesus’ granary; others are burned with unquenchable fire. Good news? Well, in theory, I suppose, it could be. You’d just have to be pretty sure that you’d turn out to be wheat, and that no one you care much about would end up in the chaff pile. So if you’re pretty sure you’ve loved God with all your heart, and your neighbor as yourself, AND you don’t mind seeing some of your neighbors burned with unquenchable fire – well, you see the difficulty. Or if you’re sure that affirming Jesus as Lord and Savior is a golden ticket, AND you don’t mind about your Jewish friends, or the half billion or so Buddhists in the world, or your dear friend Doug, who just gave you a souvenir coffee mug from his recent visit to the Church of Satan – again, you run aground, don’t you? Even if you try to take a “reasonable” approach – people who are pretty good are wheat, only the really terrible ones are chaff – before you know it, you sound just like the Pharisee who thanked God that he wasn’t a thief, a rogue, an adulterer – that he wasn’t like that tax collector over there at the other side of the temple.

Here’s one answer: make someone else pay the price. Some of us are wheat; others are chaff. Some of us get gathered into Jesus’ granary; others are burned with unquenchable fire. Good news? Well, in theory, I suppose, it could be. You’d just have to be pretty sure that you’d turn out to be wheat, and that no one you care much about would end up in the chaff pile. So if you’re pretty sure you’ve loved God with all your heart, and your neighbor as yourself, AND you don’t mind seeing some of your neighbors burned with unquenchable fire – well, you see the difficulty. Or if you’re sure that affirming Jesus as Lord and Savior is a golden ticket, AND you don’t mind about your Jewish friends, or the half billion or so Buddhists in the world, or your dear friend Doug, who just gave you a souvenir coffee mug from his recent visit to the Church of Satan – again, you run aground, don’t you? Even if you try to take a “reasonable” approach – people who are pretty good are wheat, only the really terrible ones are chaff – before you know it, you sound just like the Pharisee who thanked God that he wasn’t a thief, a rogue, an adulterer – that he wasn’t like that tax collector over there at the other side of the temple.

No, it just won’t do. There’s no way I can hear John’s message as “good news” by foisting the fire off on someone else. So, gingerly, I consider the words again. Take the metaphor seriously. Do you know what chaff actually is? It’s the “dry, scaly, protective casing” of the grain of wheat.[4] It’s not some separate, alien object. It’s part of the wheat kernel itself. But the chaff is indigestible. If you want to get to the good part of the wheat, the nutritious, rich, tasty part, the chaff – the dry, scaly, protective casing – has to be removed.

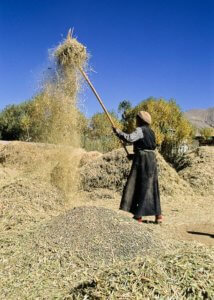

Chaff

Ah. Now we’re onto something. Do you have a dry, scaly protective casing? A hard shell that feels like it keeps you safe, but that you know, in your heart of hearts – in the rich, soft center of you, the velvet depth of your being – is separating you from living fully in the love of God? Someone is coming who will take care of that, John said. He’s going to baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire; he has his winnowing fork ready, and he’s going to use it until that hard, scaly protective casing is gone, and all that’s left of you is the soft, good center. You’ll be totally vulnerable, utterly exposed, because the pieces of your shell, all those bits of dry husk, they’re going straight into an unquenchable fire. And then He will gather you in.

Ah. Now we’re onto something. Do you have a dry, scaly protective casing? A hard shell that feels like it keeps you safe, but that you know, in your heart of hearts – in the rich, soft center of you, the velvet depth of your being – is separating you from living fully in the love of God? Someone is coming who will take care of that, John said. He’s going to baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire; he has his winnowing fork ready, and he’s going to use it until that hard, scaly protective casing is gone, and all that’s left of you is the soft, good center. You’ll be totally vulnerable, utterly exposed, because the pieces of your shell, all those bits of dry husk, they’re going straight into an unquenchable fire. And then He will gather you in.

Good news? Well – I like the gathering in part. No, seriously. When I hear John’s message this way, there’s no question that it’s good news. Of course it’s good news. He’s telling me that I am going to become the person God wants me to be. Who could want anything more?

Well – me. I could want something more, or maybe just something a little different. Because all this winnowing, all this fire – it sounds like it could hurt. Also, do you know what comes before winnowing? Threshing. The grain is crushed to loosen the husk. It can be beaten by hand; in some cultures, the wheat would be laid out on hard ground, and oxen, sheep, and other animals were driven over it, again and again, to “tread it out.”[5] Jesus doesn’t do this part, in John’s message – but, nonetheless, there’s no winnowing without it.

Good news, yes. But do I dare to hear it?

Wouldn’t it be so much easier if John had given us nice, straightforward good news, along the lines of the news the Israelites got, in our reading from Isaiah, after the long years of Babylonian oppression and exile?

I’ve redeemed you, God says; I’ve called you by name, you are mine. Don’t be afraid: the fire won’t burn you, the rivers won’t overwhelm you. I am the Lord and I am your Savior.

Everything you could possibly have wanted to hear.

But it turns out even Isaiah’s good news came at a price. To get the suffering people to listen to him, let alone take his words seriously enough to be gladdened by them, the prophet had to answer some tough questions.

For example: If God is powerful enough to rescue us now, why did He let this utter catastrophe happen to us in the first place? And all this time, through all our agony – where has God been? If it was some kind of punishment, well, we weren’t perfect, but surely we didn’t deserve this?

Isaiah didn’t avoid these questions. He answered all of them, in a way that turned Israel’s disaster into a beacon of hope, not only for Israel, but for the whole world.

Babylonian Exile

But the answers aren’t easy. Isaiah’s good news comes at the price of accepting things that are hard to accept, hearing things that are hard to hear.

In his brilliant and beautiful book, The Prophets, Abraham Joshua Heschel, the mid-20th century rabbi, scholar, Holocaust survivor, and civil rights leader, doesn’t shy away from the idea that the Babylonian exile, and God’s silence in the face of Israel’s suffering, were a consequence of Israel’s own turning away from God. The earlier prophets had cried out, again and again, of the disasters that would result from the people’s failure to do justice, to show mercy, to love God, to love their neighbors. “People act as they please,” Heschel says, “doing what is vile, abusing the weak, not realizing that they are fighting God, affronting the divine, or that the oppression of [people] is a humiliation of God.”[6] Yes, God gets angry, Heschel says. God’s anger isn’t irrational, petulant, or vindictive; it is “a free and deliberate reaction of God’s justice to what is wrong and evil.”[7]

In his brilliant and beautiful book, The Prophets, Abraham Joshua Heschel, the mid-20th century rabbi, scholar, Holocaust survivor, and civil rights leader, doesn’t shy away from the idea that the Babylonian exile, and God’s silence in the face of Israel’s suffering, were a consequence of Israel’s own turning away from God. The earlier prophets had cried out, again and again, of the disasters that would result from the people’s failure to do justice, to show mercy, to love God, to love their neighbors. “People act as they please,” Heschel says, “doing what is vile, abusing the weak, not realizing that they are fighting God, affronting the divine, or that the oppression of [people] is a humiliation of God.”[6] Yes, God gets angry, Heschel says. God’s anger isn’t irrational, petulant, or vindictive; it is “a free and deliberate reaction of God’s justice to what is wrong and evil.”[7]

This is hard to hear, isn’t it? But isn’t the possibility of divine anger the “price” of the good news of divine concern, of divine love and care for the world? “It is because [God] cares for [human beings],” Heschel says, “that [God’s] anger may be kindled against [us].”[8] In the prophetic vision, God has invited human beings into active relationship – a relationship in which, astonishingly, we have an important role to play. “The universe,” Heschel says, “is done. The greater masterpiece still undone, still in the process of being created, is history. For accomplishing God’s grand design [of a righteous world], God needs [our] help.”[9]

We Matter to God

This is good news. We matter to God; God wants us, God needs us to carry out God’s work in the world. Think about our reading from Acts. The people of Samaria had accepted the word of God; they had been baptized in Jesus’ name. But it was only after Peter and John went down to them, prayed with them, and laid their hands on them, that the people of Samaria received the Holy Spirit.[10] Peter and John, two of God’s fragile, imperfect creatures, did this work. If we matter this much to God, we can disappoint God; if God is counting on us, we can let God down. We can provoke God’s anger. God will call us back, over and over; at times, the path back may be a painful one.

And yet, and yet – even if one accepts all of this – surely, surely Israel’s horrific experience in exile was wildly disproportionate to her wrongdoing? Yes, Isaiah says. It’s true: Israel has suffered far more than she deserves. Israel’s agony, in Heschel’s words, “far exceeded her guilt .… She is the suffering servant of the Lord … [Her] suffering and agony are the birthpangs of salvation” not only for Israel itself, but for the whole world.[11]

I have chosen you; I have called you by name; you are mine. Good news, to be sure. But no one said it would be painless. Why would you expect it to be? Jesus heard this at His baptism: “‘You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.'”[12] And yet He bore the burden of all our sins. We have been called to follow Him. Following Him may be painful. Some of the pain may go well beyond anything we “deserve.” But that’s not the end of the story.

Just when we’re flat out on the threshing floor, in a scrambled mess of broken husks, Jesus comes with his winnowing fork. And do you know what? He doesn’t look fierce at all. He bends down, scoops us up, and tosses us lightly into the air. Chaff is lighter than good wheat, so some of it blows away, into the fire. He does it again and again, gently, patiently, bending, lifting, tossing – until all our chaff has blown away, and we are free of the last remaining bits of dry, scaly, protective outer shell. Free, at last, to be the people God made us to be: people who will gladden God’s heart and help God create a righteous world.

Amen.

Bibliography

The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha, Fourth Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010 (Kindle edition).

Heschel, Abraham Joshua. The Prophets. New York: Harper Perennial Classics, 2001 (original hardcover edition published by Harper & Row, 1962).

Wikipedia contributors. “Chaff.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaff (accessed January 4, 2022).

–. “Threshing.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threshing (accessed January 5, 2022).

[1] Luke 3:16-17.

[2] Luke 3:18.

[3] Luke 3:19-20.

[4] Wikipedia, “Chaff.”

[5] Wikipedia, “Threshing.”

[6] Heschel, The Prophets, 253.

[7] Heschel, 367.

[8] Heschel, 363-4.

[9] Heschel, 258.

[10] Acts 8:14-17.

[11] Heschel 189-90.

[12] Luke 3:22.