“Stay with Us”

Good morning. Please pray with me. May the words of my mouth, and the meditations of

all our hearts, be acceptable to you, oh, Lord, our rock and our redeemer. Amen.

Even before the pandemic gave us all an excuse to watch silly movies, I had a fondness

Even before the pandemic gave us all an excuse to watch silly movies, I had a fondness

for romantic comedies. In one of my favorites, the delightful movie Sliding Doors, the viewer

knows from the beginning that Gwyneth Paltrow’s boyfriend is up to no good. She’s rushing

around, getting ready for work, and he’s still in bed, pretending to be asleep. How do we know

he’s pretending? We just do. It’s obvious. But Gwyneth doesn’t see it. She leans over, gives him

a kiss on the forehead, and heads out to the office. As soon as she closes the door behind her, his

eyes pop open. He takes the phone off the hook, gets into the shower, and even if you’re seeing

the movie for the first time, you know he’s about to do something rotten. You see him. You

know who he is. But Gwyneth … Gwyneth doesn’t. Somehow, she doesn’t get it.

Will she figure it out? Well, yes. We know that, too. From the opening credits, it’s

obvious that this is a romantic comedy, not some despairing art film with subtitles. Gwyneth will

figure it out and, one way or another, things will work their way to a happy ending.

The thing that distinguishes this movie from a thousand other rom-coms is that we get

two versions of the story. In version one, Gwyneth figures out who her scoundrelly boyfriend

really is early on; in version two, it takes a whole lot longer. And the turning point, the thing that

makes all the difference, is whether she makes it onto a subway. In version one, she catches the

sliding doors as they are closing and manages to squeeze herself on board. In version two, the

doors slide shut, and the train leaves without her.

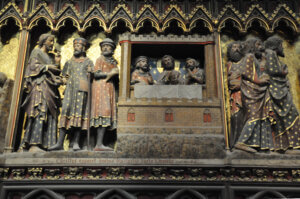

The Emmaus Road story, like Sliding Doors, announces itself as a comedy from the start, with Cleopas and his unnamed friend in the Gwyneth Paltrow role. You know these earnest, sweet, sad, and utterly clueless disciples are going to figure it out at some point, and you know they’ll be OK in the end. The deep pleasure of the story lies in watching the disciples have all the knowledge, all the evidence, and still entirely miss the point. We can identify with Cleopas and his unnamed friend, these marginal disciples who weren’t in Jesus’ inner circle. We can accept that we ourselves are “‘foolish’” and “‘slow of heart to believe.’” We can reflect on the countless times we have failed to recognize Christ walking beside us; Christ right here, right with us, today, in our midst. We can do these things because the story assures us that Jesus comes for people like us, giving us another chance to recognize Him.

The Emmaus Road story, like Sliding Doors, announces itself as a comedy from the start, with Cleopas and his unnamed friend in the Gwyneth Paltrow role. You know these earnest, sweet, sad, and utterly clueless disciples are going to figure it out at some point, and you know they’ll be OK in the end. The deep pleasure of the story lies in watching the disciples have all the knowledge, all the evidence, and still entirely miss the point. We can identify with Cleopas and his unnamed friend, these marginal disciples who weren’t in Jesus’ inner circle. We can accept that we ourselves are “‘foolish’” and “‘slow of heart to believe.’” We can reflect on the countless times we have failed to recognize Christ walking beside us; Christ right here, right with us, today, in our midst. We can do these things because the story assures us that Jesus comes for people like us, giving us another chance to recognize Him.

At the same time, though, there is suspense in the story. Jesus gives Cleopas and his

friend a chance, but, for a while, it looks like they might miss it. Jesus has been talking to them

for miles, going over (for the umpteenth time) all the things about Him in the scriptures, starting

right at the beginning, with Moses. But they still don’t get it. Finally, there’s a real cliffhanger,

where the three of them get to Emmaus and Jesus “walk[s] ahead as if he were going on.”

This is the turning point of the story; this is the Sliding Doors moment, the moment that

makes all the difference. And Cleopas and his friend manage to make it onto the train.

“Stay with us,” they say. “‘Stay with us, because it is almost evening and the day is now

nearly over.”

Stay with us. It’s getting dark. You don’t want to be out on that road all night, not with

everything going on in Jerusalem right now. Anyway, the day is nearly over; you’re not going to

get very far before you’ll have to stop. So, come stay with us.

Come stay with us. Not “Oh, wait! Now we get it! You are the risen Christ!” No, even

after all the walking and talking, all the opening of scriptures, they haven’t figured it out. But

they’ve just done the thing that makes all the difference. Jesus turns around, comes into the

house with them, and sits down to eat. He takes bread and breaks it, and, at last, they recognize

Him, just in time, before He vanishes from their sight. At which point, never mind about the

dark, never mind about the day being over: the two of them pick themselves up and walk seven

miles back to Jerusalem to rejoin their friends, tell them what happened, and see Jesus again.

In Sliding Doors, it’s easy to see why catching or missing the train is the turning point.

When she catches the train, Gwyneth also catches her boyfriend; when she misses it, he gets

away with his antics yet again.

But why, on the Emmaus Road, does the disciples’ invitation make all the difference?

What is it about “‘Stay with us’” that makes it possible for them to recognize the risen Lord?

One answer is that Jesus will never force himself on us, but He will accept any invitation

to a deeper relationship with us. He doesn’t require us to understand the scriptures, no matter

how many times we’ve had them explained to us. He doesn’t require us to accept Him as our

personal lord and savior as a precondition for relationship. After all, Cleopas and his friend were

pretty sure Jesus wasn’t the Messiah. “’But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel,’”

they say on the road. They had hoped He was their personal lord and savior; they weren’t hoping

any more. But they invited Him in, and this was enough.

And there’s also a second answer, one that focuses on the disciples themselves. What if

there’s something about giving this invitation that allows the two weary disciples to have their

“eyes opened?” Something about this movement, this gesture, that enables them to see?

Imagine, for a moment, how utterly shattered Cleopas and his friend are. They are

grieving, they are desperately disappointed, they are exhausted, and they are afraid. The day, this

sad and scary day, this third day that was supposed to bring so much, this day is nearly over.

They want to go home, eat something, and collapse into bed. Surely they aren’t in any mood to

have guests.

And yet … Have you ever experienced the relief that comes when you realize, in the

midst of your own pain, that you actually do still have the capacity to care about somebody else?

To see them?

I wonder whether Cleopas and his friend experience something like this. They lift their

eyes from their own misery, just enough to see that this stranger needs a meal and a place to lay

His head. They exchange glances: Should we …? I mean, look at this poor guy, he must be … are

you OK if we invite him to … yeah? I know we don’t know him, but he doesn’t seem like a scary

guy, and, well, we are supposed to look after the stranger in our midst. It’s a risk, for sure, but …

OK, yes, good, me too. Imagine their hearts lifting as they call out after the stranger, “urg[ing]

him strongly” to stay.

He comes in, and they’re feeling better already. They bustle about, setting a place at the

He comes in, and they’re feeling better already. They bustle about, setting a place at the

table, asking the stranger about dietary restrictions, finding a place for him to sleep, poking around in cabinets for pillows and an extra blanket. What a relief it must have been, after all they had been through, to discover that they themselves are still capable of kindness and hospitality. To find that they are able to look up and attend to someone else. To see him. To push the plate toward him and say “We’re so glad you stayed. Here, go ahead, please. Would you do the honors and break the bread?”

And, oh, the joy that follows, the pure delight.

But let me ask you to consider a question. What if something else had happened in that

cliffhanger moment? What if Cleopas and his friend hadn’t urged Jesus to stay?

We don’t know, not in any literal sense. Unlike the writer of Sliding Doors, Luke doesn’t

give us version two of the story, the version where the disciples miss the train. But what makes

Sliding Doors a comedy is that we know, from the beginning, that version two will end happily,

too. And I want to suggest that we actually do know that Cleopas and his friend would have been

OK in the end, even if they had let Jesus walk on into the gathering dusk. That’s the kind of story

this is. The writer Frederick Buechner has suggested that, “[f]rom the divine perspective,” it is

the comic, and not the tragic, that is bound to happen. “The comedy of God’s saving the most

unlikely people when they least expect it, the joke in which God laughs with man and man with

God – I believe,” Buechner writes, “that this is what is inevitable.”1

Version two might have taken longer. Cleopas and his friend might have undergone more

suffering in the meantime. But Jesus would have come for them again. He would have given

them another chance. And another, and another.

Because that’s who Jesus is. We know. We’ve seen Him. He’s here, right now, in our

midst.

Let’s invite Him to stay.

Amen.

1 Buechner, Frederick. Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale, HarperCollins: New

York, 1977. Page 72.